Study shows health benefits of tackling arsenic, chromium-6 and other pollutants at once

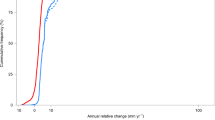

WASHINGTON – Drinking water treatment that pursues a multi-contaminant approach, tackling several pollutants at once, could prevent more than 50,000 lifetime cancer cases in the U.S., finds a new peer-reviewed study by the Environmental Working Group.

The finding challenges the merits of regulating one tap water contaminant at a time, the long-standing practice of states and the federal government.

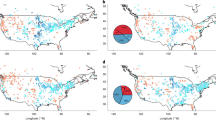

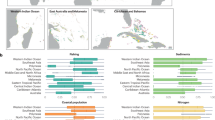

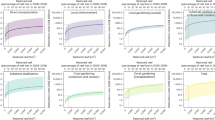

In the paper, published in the journal Environmental Research, EWG scientists analyzed more than a decade of data from over 17,000 community water systems. They found that two cancer-causing chemicals – arsenic and hexavalent chromium, or chromium-6 – often appear together in systems and can be treated using the same technologies.

If water systems with chromium-6 contamination also reduce arsenic levels to a range from 27% to 42%, it could avoid up to quadruple the number of cancer cases compared to just lowering chromium-6 levels alone, the study finds.

Treatment of drinking water for one contaminant, such as nitrate, has advantages for public health. But tackling multiple contaminants at once increases the health benefits. And those benefits can expand along with the number of pollutants treated at the same time.

“Drinking water is contaminated mostly in mixtures, but our regulatory system still acts like they appear one at a time,” said Tasha Stoiber, Ph.D., a senior scientist at EWG and lead author of the study. “This research shows that treating multiple contaminants together could prevent tens of thousands of cancer cases.”

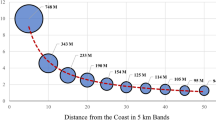

Chromium-6 and arsenic are commonly found in drinking water across the U.S. Chromium-6 has been found in drinking water served to 264 million Americans.

“Addressing co-occurring contaminants is scientifically the most sound approach, as well as an efficient way to protect public health,” added Stoiber.

In California alone, nearly eight out of 10 preventable cancer cases are linked to arsenic exposure.

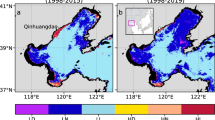

Arizona, California and Texas bear the highest burden of arsenic pollution and would gain the most from multi-contaminant water treatment efforts.

Health risks of water contaminants

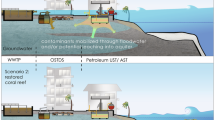

Toxic chemicals like chromium-6, arsenic and nitrate pose the greatest risks to children, pregnant people and those living in smaller communities served by water systems relying on groundwater. Systems serving these populations often rely on only one water source and the smaller communities lack the resources to demand better treatment, despite facing the most serious health harms.

Chromium-6

This cancer-causing chemical made infamous by the film “Erin Brockovich” is linked to serious health risks. Studies show even low levels in drinking water can increase the risk of stomach cancer, liver damage and reproductive harm.

In 2008, the National Toxicology Program found much higher rates of stomach and intestinal tumors in lab animals exposed to chromium-6 in water. California researchers later confirmed a higher risk of stomach cancer in workers who had been exposed.

The Environmental Protection Agency does not limit the amount of chromium-6 in drinking water. It does regulate total chromium, which includes chromium-6 and the mostly harmless chromium-3. Total chromium is set at 100 parts per billion, or ppb, for drinking water.

Arsenic

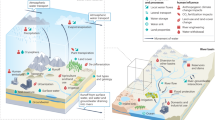

Arsenic is found in drinking water in all 50 states. It occurs in natural deposits and as a result of human activities such as mining and pesticide use. Long-term exposure is linked to serious health issues, including bladder, lung and skin cancers, as well as cardiovascular and developmental harm.

The legal federal limit for arsenic in drinking water is 10 ppb, set in 2001 based on outdated cost estimates for treatment, not on what’s safest for health. California’s public health goal is just 0.004 ppb, the level scientists say would pose no significant cancer risk over a lifetime.

Arsenic can also contaminate certain foods, especially rice and rice-based products, making clean water standards all the more important for reducing overall exposure.

Nitrate

Nitrate is one of the most common drinking water contaminants, especially downstream from agricultural areas where it enters water supplies through fertilizer and manure runoff. It’s also found in private wells, often near farms or septic systems.

Exposure to nitrate in drinking water is linked to serious health risks, including colorectal and ovarian cancer, very preterm birth, low birth weight, and neural tube defects.

The EPA set the nitrate limit at 10 parts per million in 1992 to prevent “blue baby syndrome.” But it hasn’t updated the standard in over 30 years. New research shows cancer and birth-related harms can occur at levels far below the legal limit. European studies have found increased cancer risks at nitrate levels more than 10 times lower than the EPA limit.

“Ensuring clean drinking water for all communities is about fairness and equity,” said Sydney Evans, MPH, EWG senior science analyst and a co-author of the new study.

“Communities in the U.S. that rely on groundwater are often affected by these contaminants. New water treatment technologies offer a chance to improve water quality overall. This strengthens the case for action and investment.”

Call for smarter water rules

Federal regulations still evaluate the cost and benefit of water treatment on a one-contaminant basis, a model EWG’s report calls outdated and inefficient.

Small and rural water systems often face the steepest per-person costs to implement new treatment technologies. But they’re among the most exposed to pollutants and associated risks.

These systems frequently lack the funding and technical support to upgrade aging infrastructure, leaving residents exposed to serious health threats. This level of vulnerability calls for new strategies for these communities – a boost in funding coupled with more effective regulations.

For example, nitrate, often found alongside chromium-6 in drinking water, represents a major but overlooked opportunity for health protection.

“Nitrate pollution is a public health crisis, particularly in the Midwest but also across the country,” said Anne Schechinger, EWG’s Midwest director. “The federal nitrate limit was set decades ago to prevent infant deaths, but we now know see cancer and birth complications at levels of nitrate far below that outdated standard.

“Even lowering nitrate slightly could prevent hundreds of cancer cases and save tens of millions of dollars in health care costs, especially when paired with treatment for other contaminants, such as chromium-6 and arsenic,” she said. “There’s a real cost to inaction – our health and our wallets can’t afford to wait for better treatment.”

Proven technologies like ion exchange and reverse osmosis, already used today, can remove nitrate, chromium-6 and arsenic from drinking water at the same time.

“This is about more than clean water – it’s about protecting health and advancing equity,” said David Andrews, Ph.D., acting chief science officer at EWG. “We have the engineering solutions to fix the broken drinking water system in the U.S., but we need state and federal policies to reflect the reality people face when they turn on the tap.”

Consumers concerned about chemicals in their tap water can install a water filter to help reduce their exposure to contaminants. The home filter system that’s most effective for removing chromium-6, arsenic and nitrate from water is reverse osmosis. Ion exchange technology is another option for reducing levels of these contaminants.

EWG’s water filter guide contains more information about available options. It is crucial to change water filters on time. Old filters aren’t safe, since they harbor bacteria and let contaminants through.

People can also search EWG’s national Tap Water Database to learn which contaminants are detected in their tap water.

###

The Environmental Working Group is a nonprofit, non-partisan organization that empowers people to live healthier lives in a healthier environment. Through research, advocacy and unique education tools, EWG drives consumer choice and civic action.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION

https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news-release/2025/07/ewg-reducing-multiple-tap-water-contaminants-may-prevent-over