Scientific Reports volume 15, Article number: 7414 (2025) Cite this article

- 3767 Accesses

- 8 Citations

- Metricsdetails

Abstract

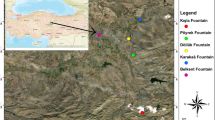

Human health is at risk from drinking water contamination, which causes a number of health problems in many parts of the world. The geochemistry of groundwater, its quality, the origins of groundwater pollution, and the associated health risks have all been the subject of substantial research in recent decades. In this study, groundwater in the west Rosetta Nile branch of the Nile Delta Aquifer is examined for drinking potential. Numerous water quality indices were applied, such as water quality index (WQI), synthetic pollution index (SPI) models, and health risk assessment (HRA) method. The limits of the measured parameters are used to test its drinking validity on the basis of WHO recommendations. TDS in the southern regions is within the desirable to allowable limits with percent 25.3% and 29.33%, respectively. Nearly all the study area has desirable value for HCO3, Al and Ba. Ca and Mg have desirable values in the center and south portion of the investigated area, whereas in the north are unsuitable. Na, Cl and SO4 fall within the desired level in the regions of the south but become unsuitable towards the north. Mn and NO3 are inappropriate except in the northwestern part. Fe is within suitable range in the southwestern and northwestern regions. Pb, Zn, Cu, and Cd were undetected in the collected samples. Regarding to WQI the study area is classified into 4 classes good, poor, very poor and unfit for drinking water from south to north. According to SPI model, 20%, 18.7%, 18.7%, 8% and 34.6% of water samples are suitable, slightly, moderately, highly polluted and unfit, respectively from south to north. Based on HRA, Children are the most category endangered with percent 14.7% of the overall samples obtained, followed by females and males with percent 12% and 8%, respectively. This study offers insights into the conservation and management of coastal aquifers’ groundwater supplies. These findings have significant implications for developing strategies and executing preventative actions to reduce water resource vulnerability and related health hazards in West Nile Delta, Egypt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sustainable groundwater management through water quality index and geochemical insights in Valsad India

Article Open access13 March 2025

Spatiotemporal variations in the levels of toxic elements in drinking water of Sivas, Türkiye, and an ecotoxicological risk assessment

Article Open access24 March 2025

A decadal analysis of drinking water quality and nitrate-related health risk assessment in groundwater sources: a case study of Poldasht County, Northwest Iran

Article Open access05 February 2026

Introduction

In recent years, rapid urbanization and population growth, stress on natural resources, and global climate change have caused the demand for water to increase. Sustainable water resource management is becoming increasingly important to meet this demand. It is critical to manage water resources globally since groundwater is essential for meeting human needs and for sustaining life1,2,3,4. Furthermore, unregulated exploitation of groundwater resources has resulted in water shortages over recent decades, which has adversely affected groundwater quality and levels5,6,7,8,9,10. Salinization is a significant issue in many coastal regions globally, particularly in semi-arid and arid areas. It is seen as a crucial and visible issue that threatens future water resources and reduces water quality. Groundwater salinization is a key concern because it restricts water availability for both agricultural and urban needs, impacting the resilience and sustainability of coastal areas. An increase in total dissolved solids (TDS) or chloride (Cl) levels is a clear indicator of salinization11,12,13. The issue of water quality has garnered significant attention in coastal aquifers worldwide due to the aforementioned reasons for example, Thriassion Plain and Eleusis Gulf, Greece14, north Kuwait15, China15, Bangladesh16, Spain17, Mexico18, and others. As groundwater quality is equally important as its quantity, it is crucial to carefully assess it.

Heavy metals pose a toxic threat to human health and ecosystems when their concentrations surpass established limits as they can disrupt ecological systems, endanger human health, and worsen the quality of groundwater. Specific heavy metals, including copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), and chromium (Cr), are vital for metabolic processes in traces quantity, but become hazardous at high levels. In contrast, metals such as cadmium (Cd) are toxic even at minimal concentrations19,20. Tackling the presence of trace element-contaminated water resources is crucial for protecting both the ecosystem and human health21. Additionally, understanding the environmental behavior of these trace elements, including their transfer, fate, persistence, and the health risks they pose to consumers through the food chain, is vital. The health impacts of these elements are significantly influenced by factors such as their behavior, specific chemical composition, and binding state. Gaining insight into these factors is the key to assessing the potential risks of trace elements and devising effective strategies to minimize their harmful effects22,23. Controlling and mitigating these harmful effects can be achieved by monitoring heavy metal distribution, concentration, and health risks regularly.

Evaluating groundwater quality is a fundamental approach for ensuring the sustainable management of this essential resource. Various methodologies have been employed to assess groundwater quality, including stoichiometric, graphical, index-based, and inferential chemometric techniques, which are commonly used to analyze and monitor groundwater conditions and hydrogeochemical properties24,25,26. Additionally, advanced tools such as clustering, regression analysis, neural networks, and machine learning algorithms have been incorporated to observe and predict water quality trends effectively27,28,29. Given the variety of hydrochemical criteria, the water quality index (WQI) technique serves as an effective tool for evaluating groundwater quality. Due to its comprehensive calculation method, assessing groundwater quality through multiple hydrochemical parameters is considered a more reliable and robust approach. As a result, WQIs have been widely utilized in groundwater quality assessments. The most frequent techniques for assessing water quality are the WQI for drinking and synthetic pollution index (SPI). The Water Quality Index (WQI) for drinking water and the Synthetic Pollution Index (SPI) are effective tools for measuring and evaluating overall water quality, offering a more comprehensive approach than traditional techniques for evaluating the quality of water. Each of the two types of standard water quality index models (WQI and SPI) measure the cumulative impact of different physicochemical variables on groundwater quality based on weight and rate. Each physicochemical parameter is weighed according to its influence on drinking water quality30,31. Since many people rely on groundwater for drinking and other household purposes, high levels of nitrate in drinking water can result in serious health risks32,33,34. Therefore, health risk assessment (HRA) based on nitrate concentration was applied as drinking water quality criteria35,36,37. Combining water quality indices with GIS techniques provides the most effective method for detecting and visualizing changes in groundwater facies. Several studies have applied water quality indices (WQI and SPI) and HRA methods to evaluate groundwater quality for human use in various regions, and these techniques have proven successful. For instance, studies have been conducted on Makkah Al-Mukarramah Province (Saudi Arabia)38, coastal plain in Nigeria23, dumpsite in Awka (Nigeria)22, El Fayoum depression (Egypt)30, El Kharga Oasis (Egypt)39, and Central Nile Delta Region (Egypt)40.

The quaternary aquifer, coastal aquifer, is considered the main source of groundwater in the area west of Rosetta branch. Based on the previous studies, the groundwater within the study area exposed to several factors, which may lead to increase signs of groundwater quality deterioration. These factors are mainly attributed to anthropogenic activities and sea water intrusion12. Moreover, most previous studies conducted west of the Nile Delta have primarily focused on the morphological and geological features of the terrain41,42,43,44. Additionally, water sources have been examined in terms of their geochemical properties and suitability for irrigation purposes8,12,45,46. However, limited attention has been given to evaluating the quality of groundwater for drinking purposes within the study area. As a result, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the suitability of groundwater for human consumption in this region.

Based on the aforementioned objectives, this study aimed to evaluate the quality of groundwater for drinking purposes in the region west of the Nile Delta’s Rosetta branch. This study was conducted to develop geospatial maps of physicochemical parameters in groundwater to determine the quality suitability of drinking water. Furthermore, in order to assess the water quality from the aspect of human health, two typical water quality index models are used, namely water quality index (WQI) and synthetic pollution index (SPI). In order to analyze the data concerning water quality, descriptive statistics and correlation matrices were applied. Eventually, human health risk (HRA) was assessed in the study region via contaminated water consumption by adults (males and females) and children. It is expected that this study will assist decision makers in identifying vulnerable zones and optimizing monitoring networks for groundwater quality.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Scientists-Underground-Fix-PFAS-Drinking-Water-FT-DGTL0126-8a7f79e48b49459390a775a27583088e.jpg)