Heat waves and cold spells are now more common on the Great Lakes, according to U-M research, with implications for the region’s weather, economy and ecology.

Summary:Extreme heat waves and cold spells on the Great Lakes have more than doubled since the late 1990s, coinciding with a major El Niño event. Using advanced ocean-style modeling adapted for the lakes, researchers traced temperature trends back to 1940, revealing alarming potential impacts on billion-dollar fishing industries, fragile ecosystems, and drinking water quality.

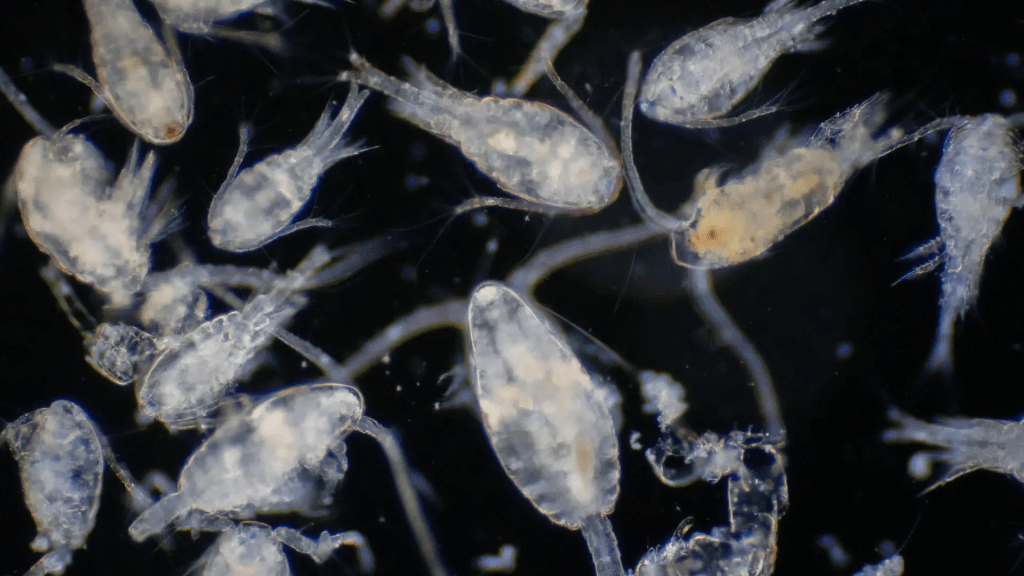

Great Lakes temperature extremes have surged since the late ’90s, threatening ecosystems, fisheries, and water quality. Advanced modeling now offers a detailed history back to 1940 and could help forecast future risks. Credit: Shutterstock

Heat waves and cold spells are part of life on the Great Lakes. But new research from the University of Michigan shows that is true today in a fundamentally different way than it was even 30 years ago.

“The appearance of these extreme temperatures is increasing,” said Hazem Abdelhady, a postdoctoral research fellow in the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, or SEAS. “For most lakes, the appearance is up more than 100% compared with before 1998.” That timing is significant because it coincides with the 1997-1998 El Niño, which is one of the strongest on record, he added.To reveal this trend, Abdelhady and his colleagues developed a state-of-the-art approach to modeling the surface temperature of the Great Lakes, which allowed them to study heat waves and cold spells dating back to 1940. The surface water temperature of the Great Lakes plays an important role in the weather, which is an obvious concern for residents, travelers and shipping companies in the region.But the uptick in extreme temperature events could also disrupt ecosystems and economies supported by the lakes in more subtle ways, Abdelhady said.

“These types of events can have huge impacts on the fishing industry, which is a billion-dollar industry, for example,” Abdelhady said. Tribal, recreational and commercial fishing in the Great Lakes account for a total value of more than $7 billion annually, according to the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

While fish can swim to cooler or warmer waters to tolerate gradual temperature changes, the same isn’t always true for sudden jumps in either direction, Abdelhady said. Fish eggs are particularly susceptible to abnormal temperature spikes or drops.

Hot and cold streaks can also disrupt the natural mixing and stratifying cycles of the lakes, which affects the health and water quality of lakes that people rely on for recreation and drinking water.Now that the researchers have revealed these trends on each of the Great Lakes, they’re working to build on that to predict future extreme temperature events as the average temperature of the lakes — and planet — continue to warm. In studying those events and their connections with global climate phenomena, such as El Niños and La Niñas, we can better prepare to brace for their impact, Abdelhady said.

“If we can understand these events, we can start thinking about how to protect against them,” Abdelahdy said.

The study was conducted through the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research, or CIGLR, and published in Communications Earth & Environment, part of the Nature journal family. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation, its Global Centers program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA.

Capturing the greatness of the lakes

One of the challenges of this work was the size of the problem itself. Although researchers have developed computer models that can simulate processes in most lakes around the world, the Great Lakes aren’t most lakes.

For starters, they’re an interconnected system of five lakes. They also contain more than a fifth of the world’s fresh surface water. And the length of their shoreline is comparable to that of the U.S.’s entire Atlantic coast — including the gulf states.In many regards, the Great Lakes have more in common with coastal oceans than with other lakes, said study coauthor Ayumi Fujisaki-Manome, who is an associate research scientist with SEAS and CIGLR.

“We can’t use the traditional, simpler models for the Great Lakes because they really don’t do well,” Fujisaki-Manome said.

So Abdelhady turned to modeling approaches used to study coastal oceans and tailored them for the Great Lakes. But there was also a data hurdle to overcome in addition to the modeling challenges.

Satellites have enabled routine direct observations of the Great Lakes starting about 45 years ago, Fujisaki-Manome said. But when talking about climate trends and epochs, researchers need to work with longer time periods.

“The great thing with this study is we were able to extend that historical period by almost double,” Fujisaki-Manome said.

By working with available observational data and trusted data from global climate simulations, Abdelhady could model Great Lakes temperature data and validate it with confidence back to 1940.”That’s why we use modeling a lot of the time. We want to know about the past or the future or a point in space we can’t necessarily get to,” said coauthor Drew Groneworld, an associate professor in SEAS and a leader of the Global Center for Climate Change and Transboundary Waters. “With the Great Lakes, we have all three of those.”

David Cannon, an assistant research scientist with CIGRL, and Jia Wang, a climatologist and oceanographer with NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, also contributed to the study. The study is a perfect example of how collaborations between universities and government science agencies can create a flow of knowledge that benefits the public and the broader research community, Gronewold said.

The team’s model is now available for other research groups studying the Great Lakes to explore their questions. For the team at U-M, its next steps are using the model to explore spatial differences across smaller areas of the Great Lakes and using the model to look forward in time.

“I’m very curious if we can anticipate the next big shift or the next big tipping point,” Gronewold said. “We didn’t anticipate the last one. Nobody predicted that, in 1997, there was going to be a warm-winter El Niño that changed everything.”

CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/08/250813083616.htm