Scientists estimate that bottled water drinkers swallow up to 90,000 more microplastic particles per year than those who stick to tap water.

Source:Concordia University

Summary:A chance encounter with plastic waste on a tropical beach sparked a deep investigation into what those fragments mean for human health. The research reveals that bottled water isn’t as pure as it seems—each sip may contain invisible microplastics that can slip through the body’s defenses and lodge in vital organs. These tiny pollutants are linked to inflammation, hormonal disruption, and even neurological damage, yet remain dangerously understudied.Share:

FULL STORY

Thailand’s Phi Phi Islands are known for their crystal-clear waters and white sand, not for launching advanced scientific research. Yet for one environmental scientist, the contrast between natural beauty and pollution sparked a major career shift from business to environmental science.

“I was standing there looking out at this gorgeous view of the Andaman Sea, and then I looked down and beneath my feet were all these pieces of plastic, most of them water bottles,” she says.

“I’ve always had a passion for waste reduction, but I realized that this was a problem with consumption.”

Armed with years of experience as co-founder of ERA Environmental Management Solutions, a company specializing in environmental, health and safety software, she returned to Concordia University to pursue a PhD on plastic waste. Her recent paper in the Journal of Hazardous Materials explores how single-use plastic water bottles pose potential health risks that remain largely overlooked in scientific research.

Hidden Hazards of Bottled Water

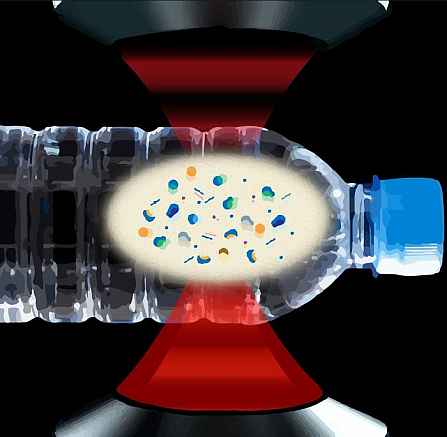

In an extensive review of more than 140 studies, the research reveals that people consume between 39,000 and 52,000 microplastic particles every year, and those who drink bottled water take in roughly 90,000 more than tap water users.

These microplastics are tiny fragments, often invisible to the eye. A typical particle measures between one micron (a thousandth of a millimeter) and five millimeters, while nanoplastics are even smaller. The contamination begins during manufacturing, transportation, and storage, when low-quality plastics release microscopic fragments — especially when exposed to sunlight and fluctuating temperatures. Unlike microplastics from food sources, those in bottled water are ingested directly.

Inside the Human Body

Once consumed, these particles can travel throughout the body. Studies indicate that microplastics can cross biological barriers, enter the bloodstream, and accumulate in organs. This may cause chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, hormonal disruption, reproductive impairment, neurological issues, and even some cancers. However, the long-term impact remains uncertain due to limited standardized testing and measurement techniques.

The researcher highlights that current detection tools vary in precision and capability. Some methods can spot smaller particles but cannot identify their composition, while others analyze chemical makeup but miss the tiniest plastics. The most advanced systems are both expensive and difficult to access, hindering consistent global study.

Rethinking Plastic Use Through Education

Despite growing environmental laws aimed at reducing plastic pollution, most regulations target items like shopping bags, straws, and packaging. Single-use water bottles often escape similar scrutiny.

“Education is the most important action we can take,” she says. “Drinking water from plastic bottles is fine in an emergency but it is not something that should be used in daily life. People need to understand that the issue is not acute toxicity — it is chronic toxicity.”

Chunjiang An, associate professor, and Zhi Chen, professor, in the Department of Building, Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Gina Cody School of Engineering and Computer Science contributed to this paper.

This research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Concordia University.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/10/251006051131.htm