WASHINGTON – New data released by the Environmental Protection Agency shows an additional 6.5 million Americans have drinking water contaminated by the toxic “forever chemicals” known as PFAS. It brings the total number of people at risk of drinking this contaminated tap water to about 165 million across the U.S.

That’s a 4% increase in the number of Americans with verified PFAS-polluted water in just the last few months. Exposure to PFAS is linked to cancer, reproductive harm, immune system damage and other serious health problems, even at low levels.

“It is impossible to ignore the growing public health crisis of PFAS exposure. It’s detectable in nearly everyone and it’s found nearly everywhere, including the drinking water for a huge segment of the population,” said David Andrews, Ph.D., acting chief science officer at the Environmental Working Group.

“The documented extent of PFAS contamination of the country’s water supply highlights the enormous scale of contamination,” he added.

The EPA’s new findings come from tests of the nation’s drinking water supply conducted as part of the Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule, or UCMR 5, which requires U.S. water utilities to test drinking water for 29 individual PFAS compounds.

Protections under threat

In 2024, the EPA finalized first-time limits on six PFAS in drinking water, which help tackle forever chemicals contamination – but these standards are now at risk.

The EPA has said it will roll back limits on four PFAS in drinking water, leaving those chemicals unregulated. It plans to only retain standards for the two most notorious chemicals, PFOA and PFOS. These maximum contaminant levels or MCLs, set enforceable standards for the amount of contaminants allowed in drinking water.

Even with keeping the PFOA and PFOS MCLs in place, rolling back the four other limits will make it harder to hold polluters responsible and ensure clean drinking water.

In addition, the EPA’s plan to reverse the four science-based MCLs likely contradicts an anti-backsliding provision in the Safe Drinking Water Act. That law requires any revision to a federal drinking water standard “maintain, or provide for greater, protection of the health of persons.”

“It’s worrying to see the EPA renege on its commitments to making America cleaner and safer, especially as it ignores its own guidelines to do so,” said Melanie Benesh, EWG’s vice president for government affairs.

Widespread PFAS pollution

The Trump administration’s PFAS standards rollback could grant polluters unchecked freedom to release toxic forever chemicals into U.S. waterways, endangering millions of Americans.

EWG estimates nearly 30,000 industrial polluters could be discharging PFAS into the environment, including into sources of drinking water. Restrictions on industrial discharges would lower the amount of PFAS ending up in drinking water sources.

“Addressing the problem means going to the source. For PFAS, that’s industrial sites, chemical plants and the unnecessary use of these chemicals in consumer products,” said Andrews.

Health risks of PFAS exposure

PFAS are toxic at extremely low levels. They are known as forever chemicals because once released into the environment, they do not break down and can build up in the body. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has detected PFAS in the blood of 99 percent of Americans, including newborn babies.

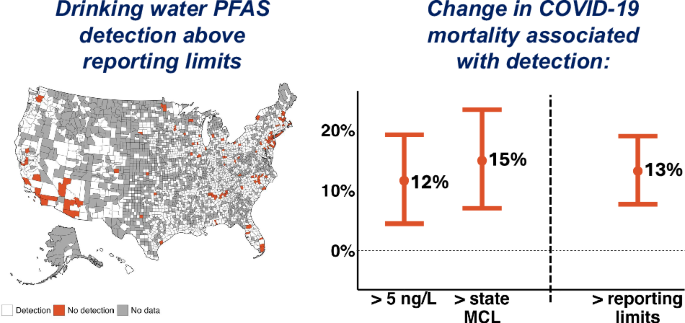

Very low doses of PFAS have been linked to suppression of the immune system. Studies show exposure to PFAS can also increase the risk of cancer, harm fetal development and reduce vaccine effectiveness.

For over 30 years, EWG has been dedicated to safeguarding families from harmful environmental exposures, holding polluters accountable and advocating for clean, safe water.

“Clean water should be the baseline,” Andrews said, “The burden shouldn’t fall on consumers to make their water PFAS-free. While there are water filters that can help, making water safer begins with ending the unnecessary use of PFAS and holding polluters accountable for cleanup.”

For people who know of or suspect the presence of PFAS in their tap water, a home filtration system is the most efficient way to reduce exposure. Reverse osmosis and activated carbon water filters can be extremely effective at removing PFAS.

EWG researchers tested the performance of 10 popular water filters to evaluate how well each reduced PFAS levels detected in home tap water.

###

The Environmental Working Group is a nonprofit, non-partisan organization that empowers people to live healthier lives in a healthier environment. Through research, advocacy and unique education tools, EWG drives consumer choice and civic action.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Fewer-Disinfection-Byproducts-BottledWater-FT-DGTL0226-bb7e2b2a08ab4dde974c35caf14eb2c9.jpg)